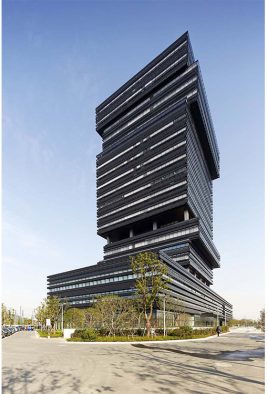

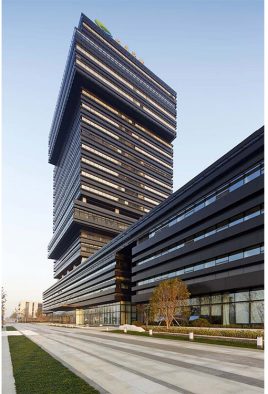

a second network embracing history, smalllness, and complexity:

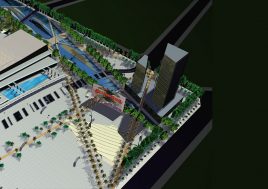

BAU193 Chengdu West New District

Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, China

Discipline

PlanningTypology

Urban planningCity

Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, ChinaDate

2004Status

Second prize, invited competitionClient

Chengdu Qing Yang GovernmentProgram

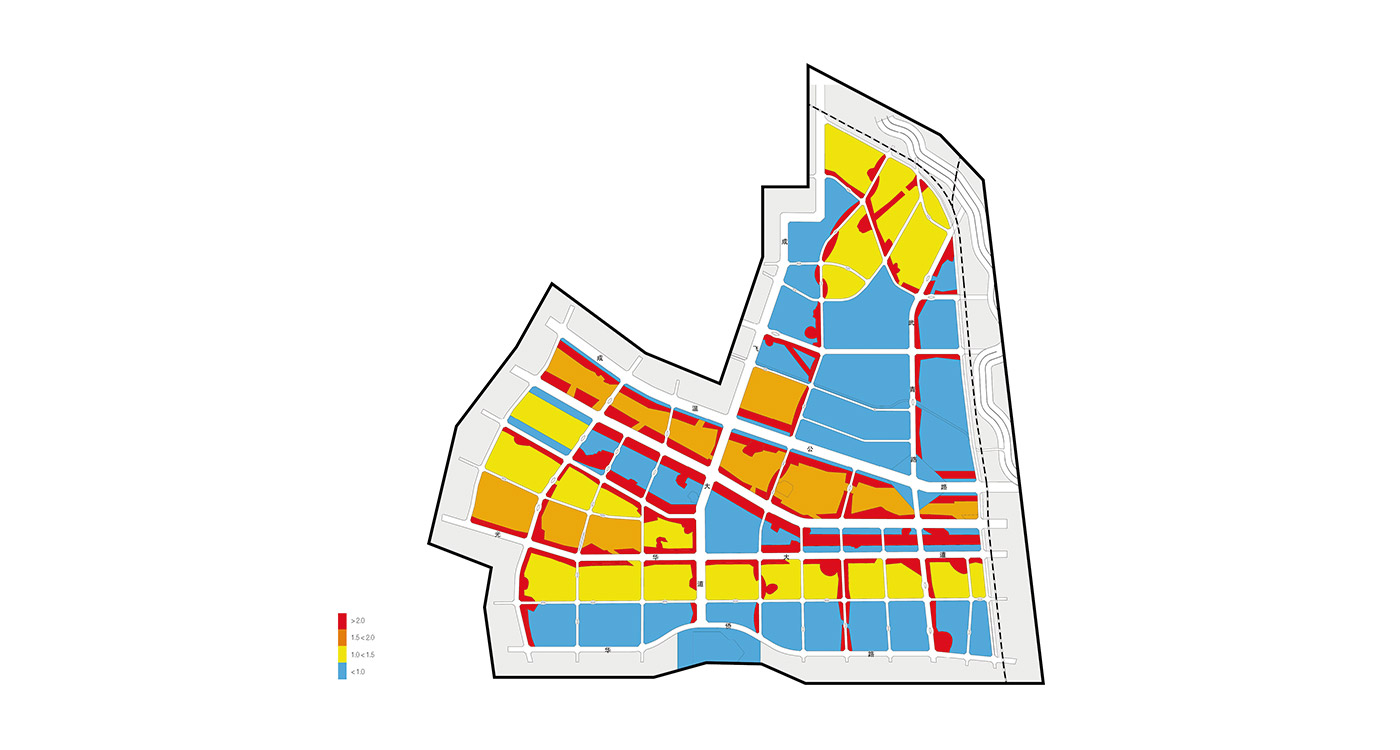

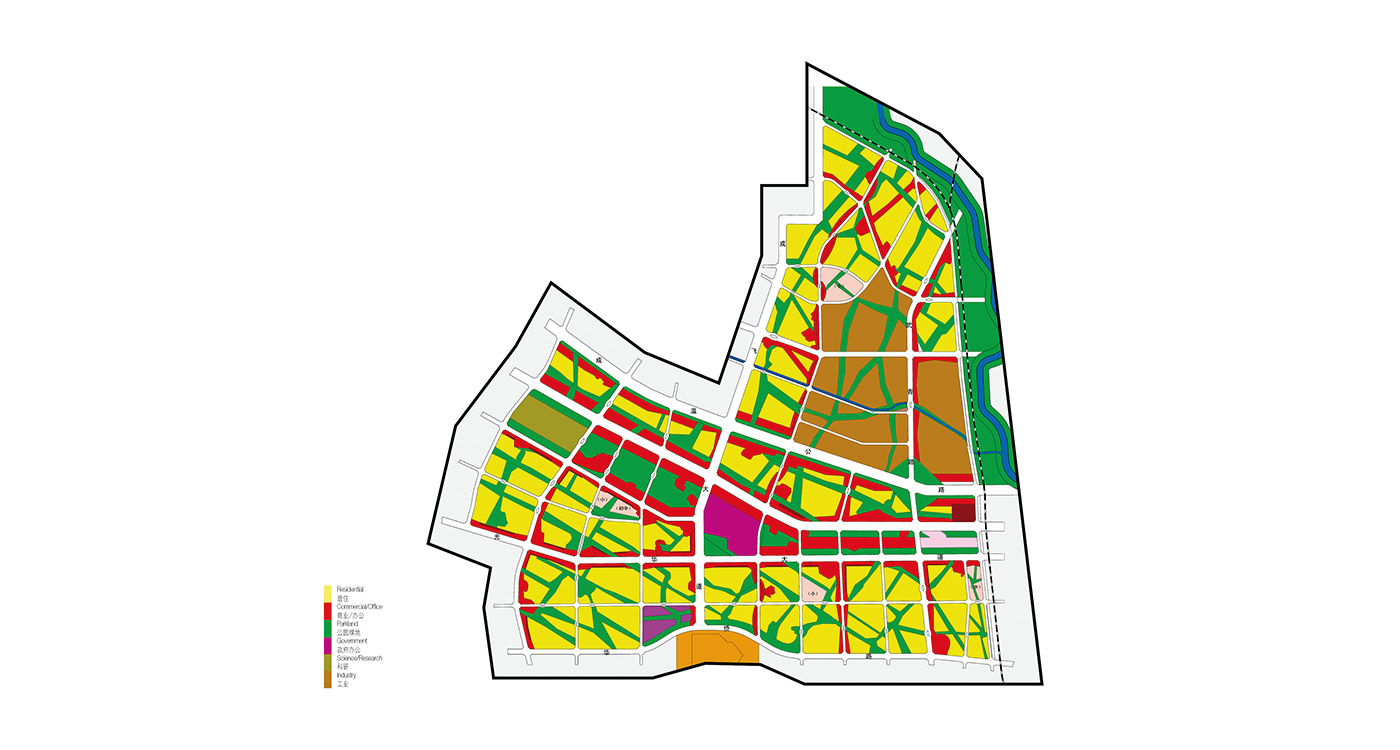

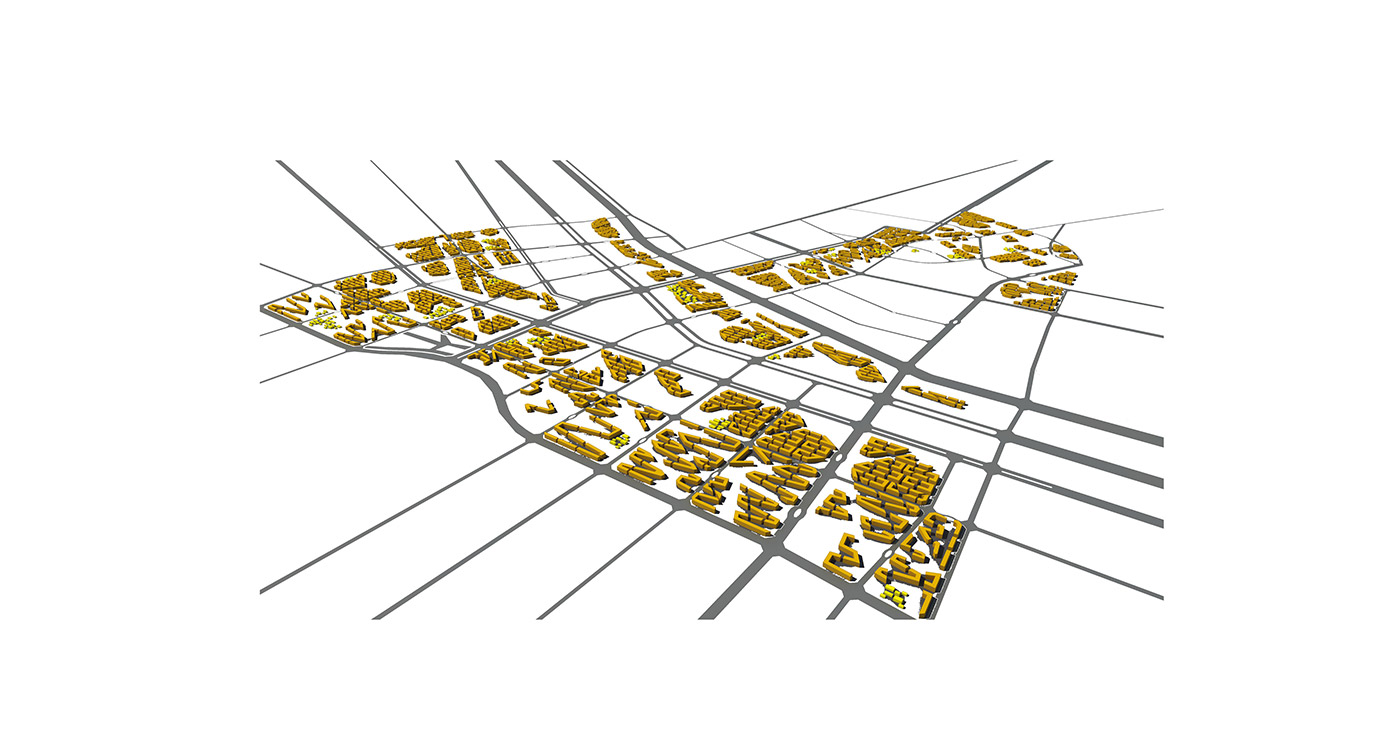

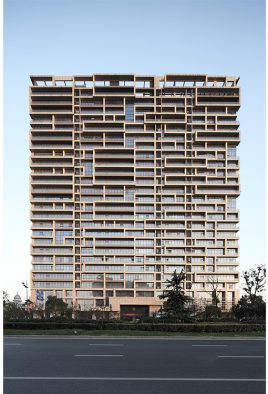

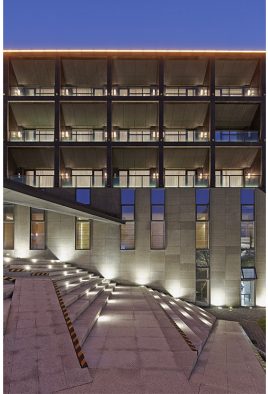

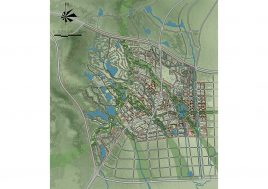

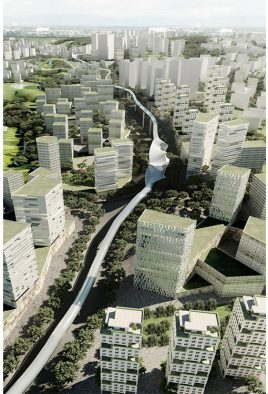

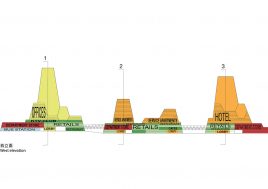

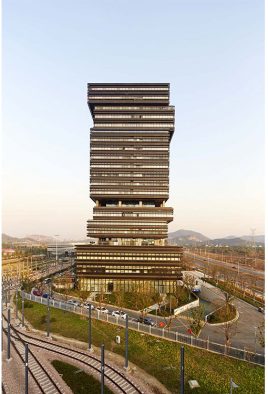

New district for 120,000 populationWithout the benefit of national guidelines or clear local policies, Chinese city governments are planning increasingly high urban densities. However, high-density building combined with gigantic scale single land-use zones and the tendency to create enclave developments easily results in socially unsustainable cities. Due to the exclusion of dissimilar programs, the resulting new residential zones are lifeless, not only inside their gated communities but also on the streets. The same can be said for the new commercial zones, particularly when office parks prevail. Paradoxically the increasing of the total floor area (FAR) of these districts results in a reduction of public life at ground level.

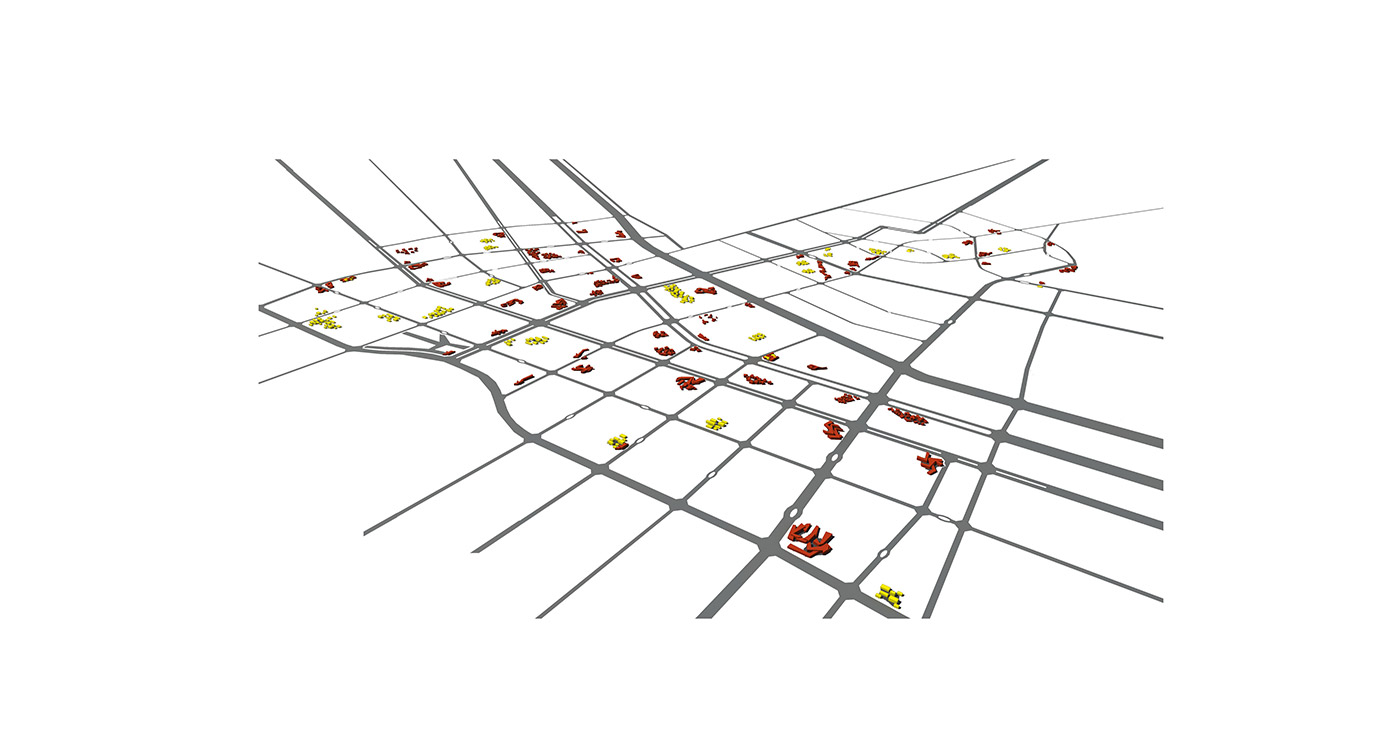

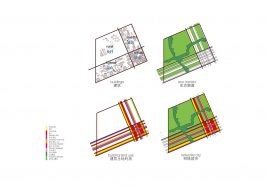

If the fervor for gigantic zoning and enormous enclaves cannot be abated, should a reduction in FAR be considered? Can the gigantic residential zone be tempered by a minimal insertion of commercial zoning, without developers and governments lessening their profits? Can remnants of history, smallness, and complexity be maintained to sustain social, economic, and cultural activity in new Chinese urbanism?

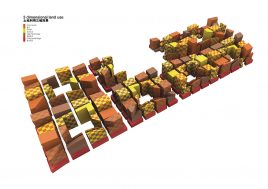

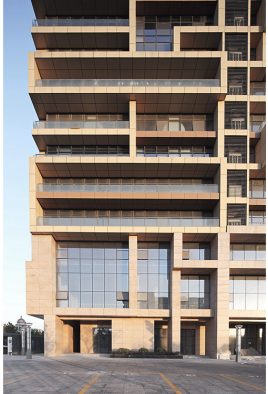

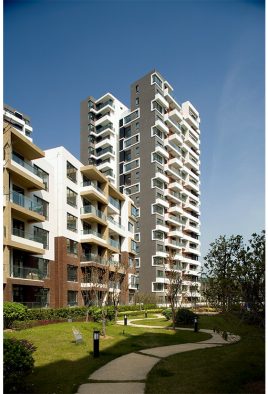

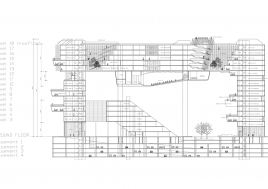

Reducing the FAR from 1.6 to 1.0 generally decreases buildings from average 11 storeys height to average 5 storeys. It shortens the required sunlight distance between residential buildings from an average 40m to average 18m. It multiplies by four the number of households living on ground and second floors. This results in housing projects with markedly more human activity at ground level, particularly if the ground floor apartments have direct access to external space. However, lowering the FAR reduces the commercial value of land; a significant compromise for politicians seeking finance with which to build demonstrable achievements within their three-year terms of office.

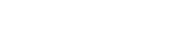

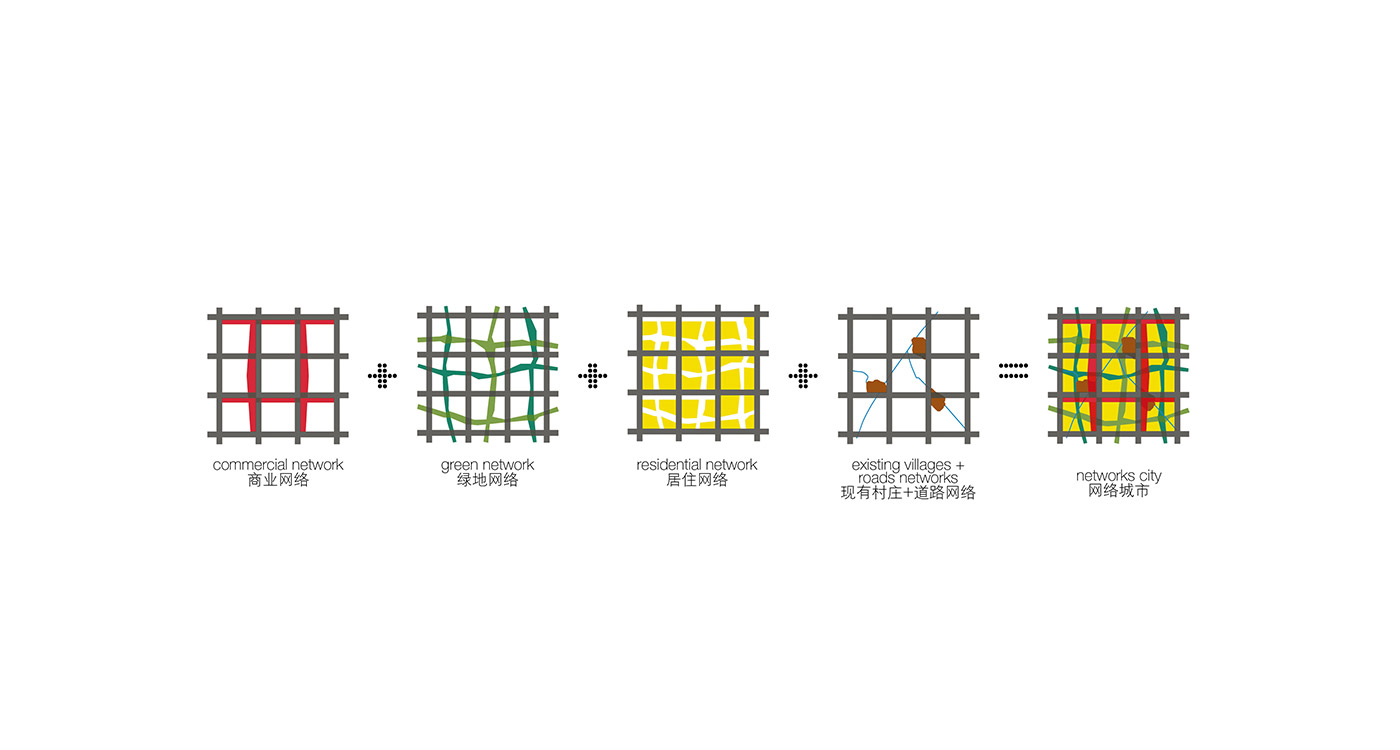

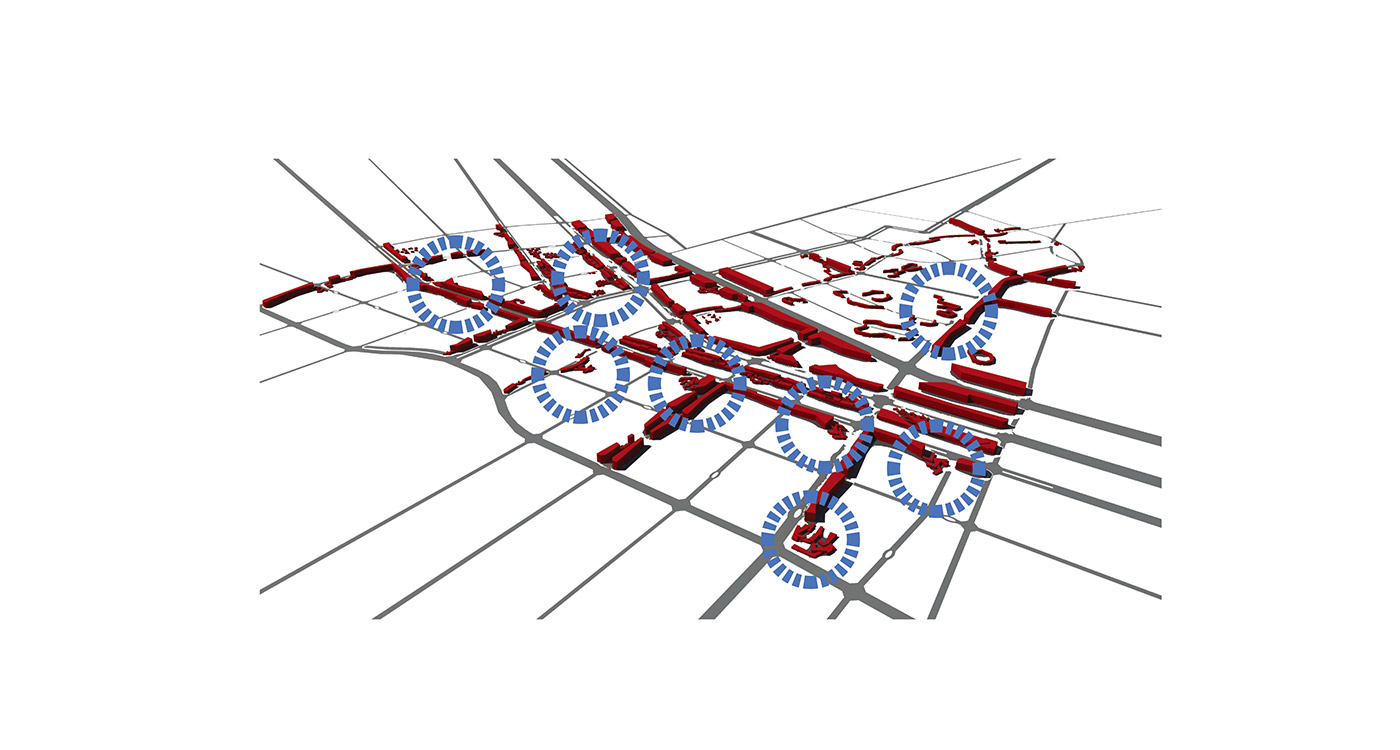

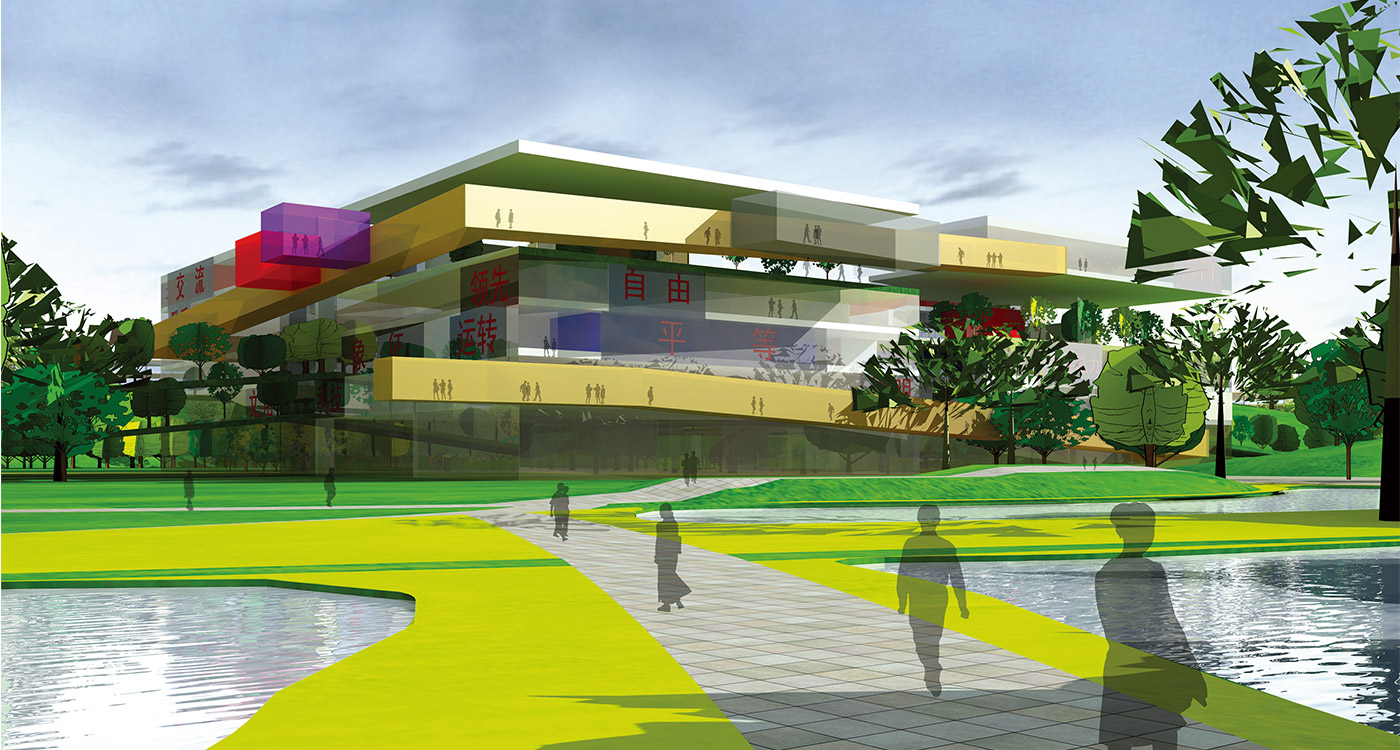

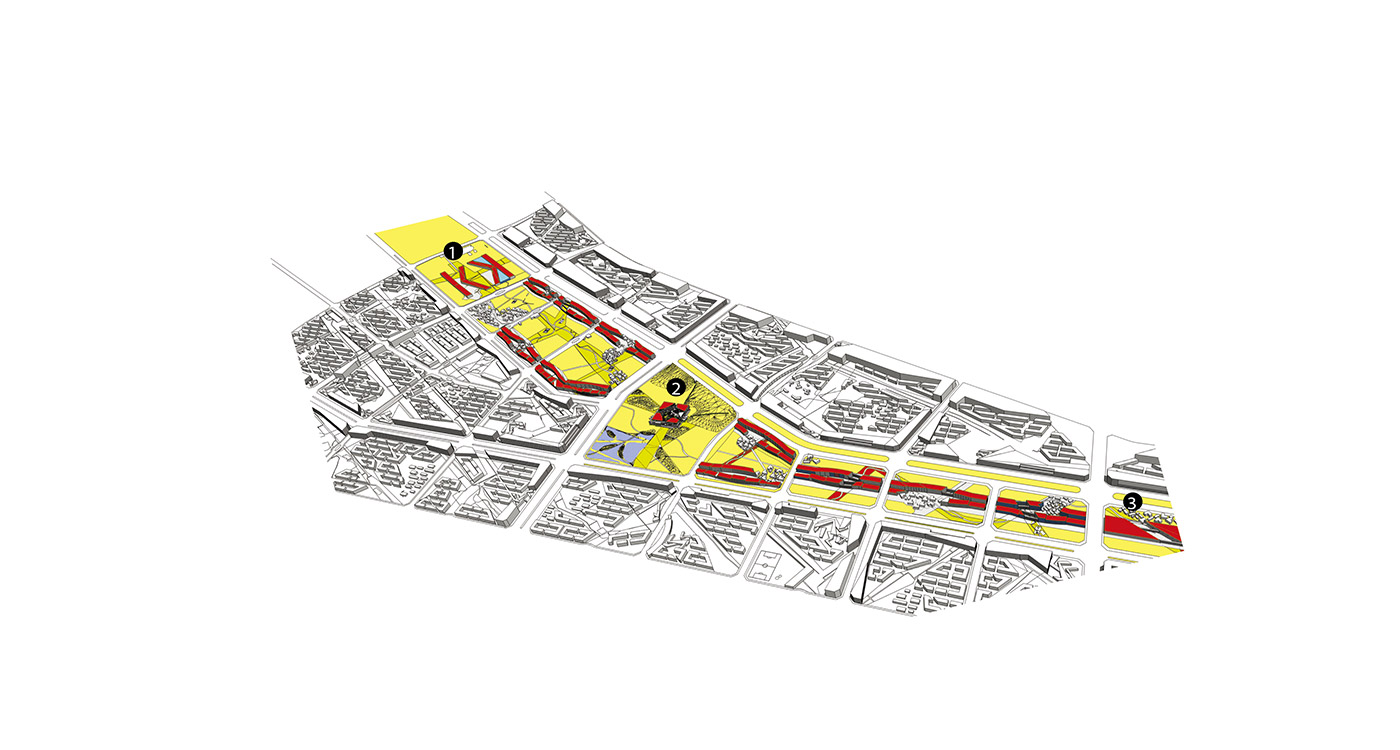

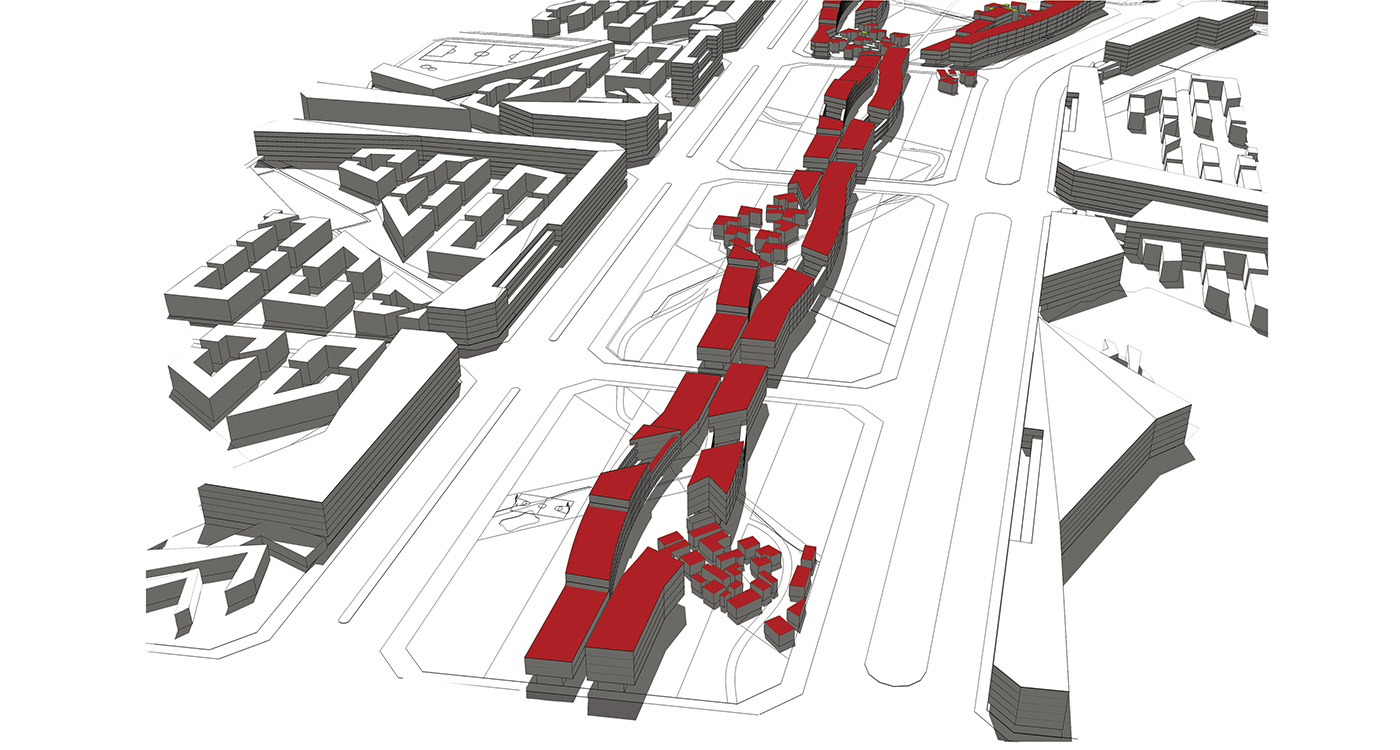

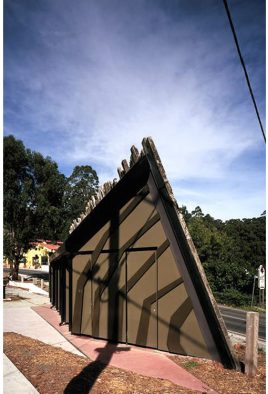

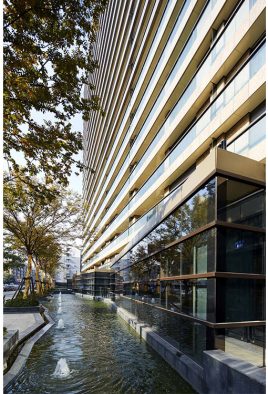

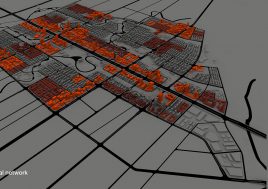

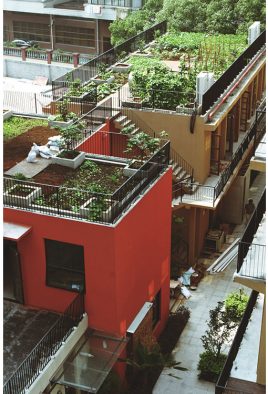

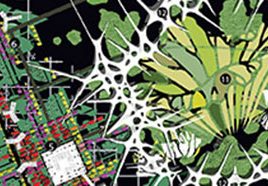

The existing street life in this peripheral district of Chengdu confirmed the city’s reputation as one of China’s most social and leisure orientated cultures. The streets here are occupied with outdoor dining, tea drinking and mahjong playing. By incorporating a continuous network of commercial zoning, street life can potentially emerge in the new residential district. This network can accommodate programs including entertainment, services, retail, offices, production, and housing in alternative typologies. The network can endure constant programmatic and physical change whilst the quiet housing enclaves behind undoubtedly remain static.

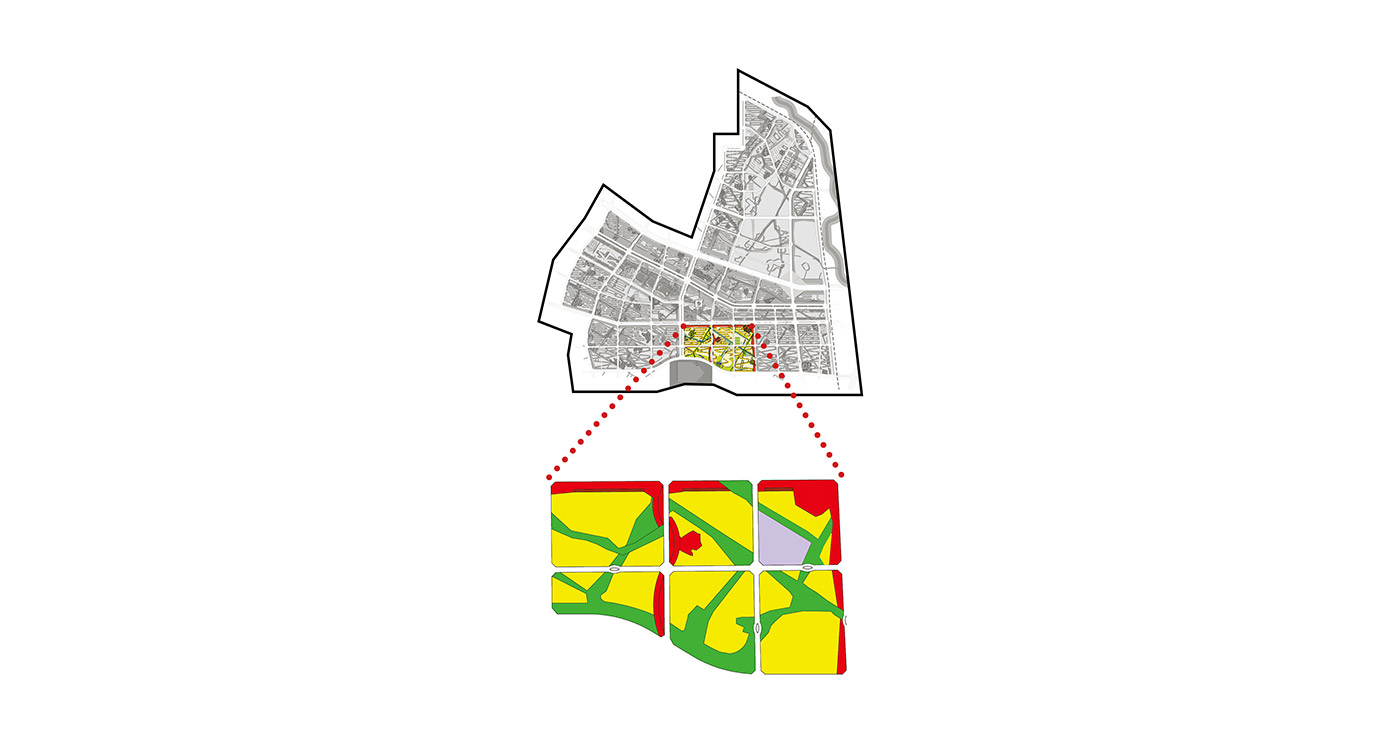

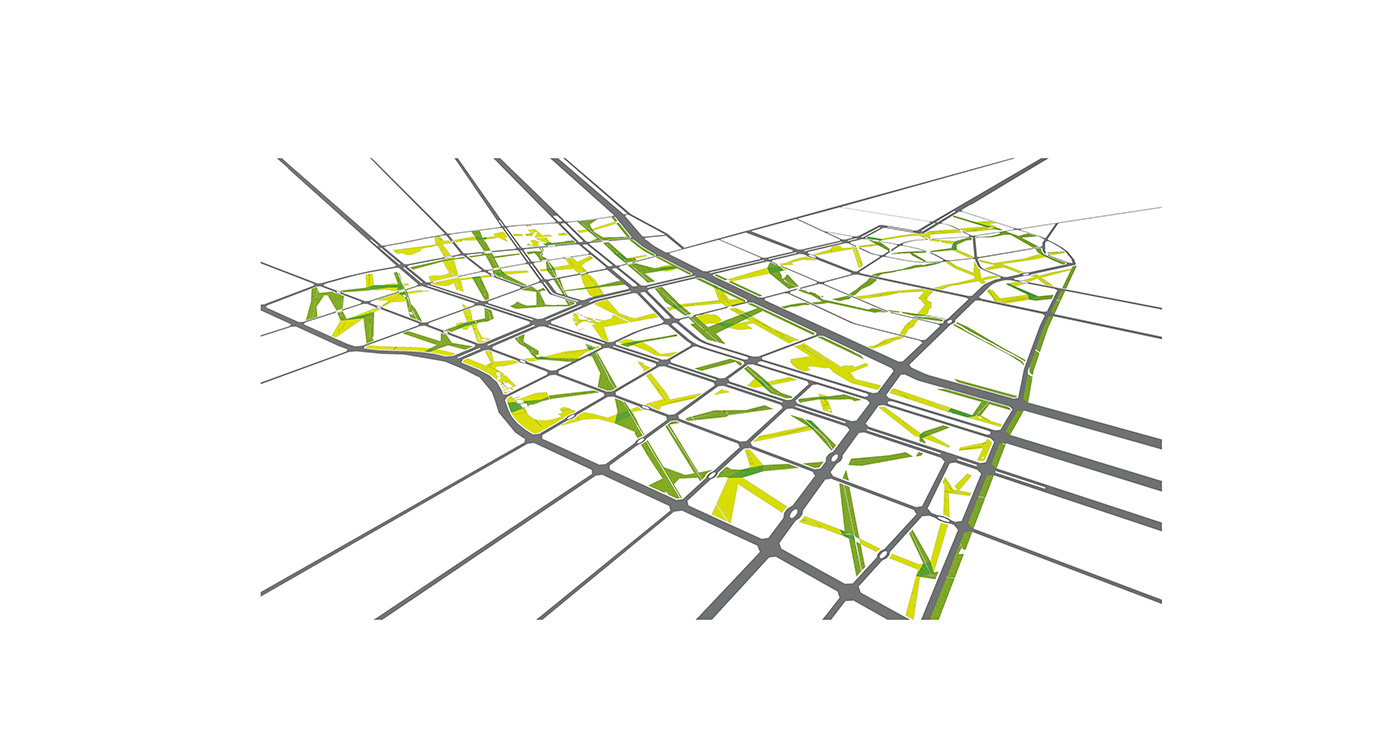

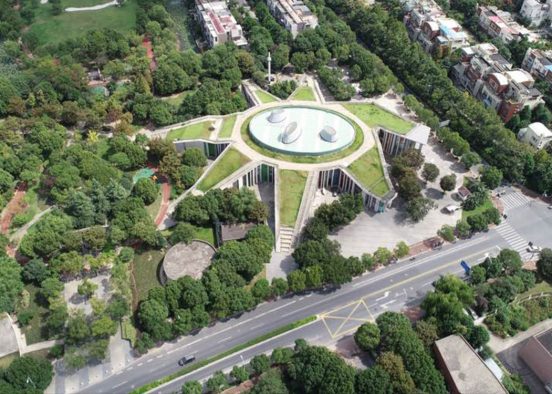

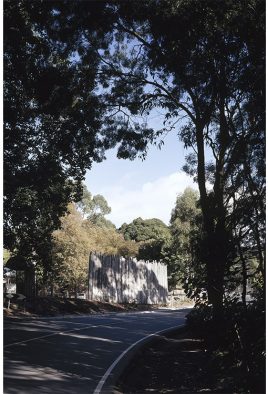

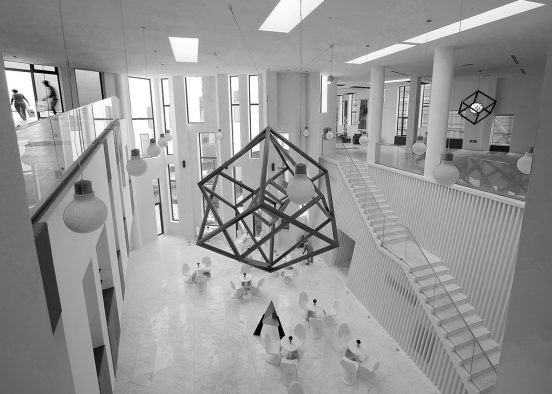

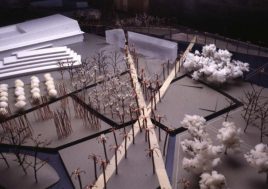

The commercial network can be designed to absorb and conserve many existing villages. The villages are places of spatial complexity, small scale, and history. These are qualities which have unfortunately disappeared from Chengdu. The scale of the buildings in the villages gives them the flexibility to adapt to the changing needs of the district. To create adequate public space for Chengdu’s street culture we have proposed sequences of sidewalks and lanes, similar in form to traditional boat-shaped streets.

In residential districts the market value of commercial property remains lower than that of residential property until the district is largely built and occupied. Thus politicians, aiming to maximize the value of land sales to developers, frequently exclude adequate commercial land use within residential zones. Once the need for commercial programs arises, the FAR has been filled with residential buildings, and it is too late to build commercial buildings. The only remaining option is to convert apartments into commercial spaces. This is however difficult for many reasons. Firstly, all housing buildings are located within enclaves. Changes therefore require the permission of hundreds of enclave neighbors; a NIMBY (not in my back yard) scenario usually prevails. Secondly, most housing buildings within the enclaves cannot be easily opened onto a public street due to the master planning of internal roads. Thirdly, almost all new Chinese apartment buildings have low ceilings and are compartmented by load-bearing wall construction, not suitable for many commercial uses.

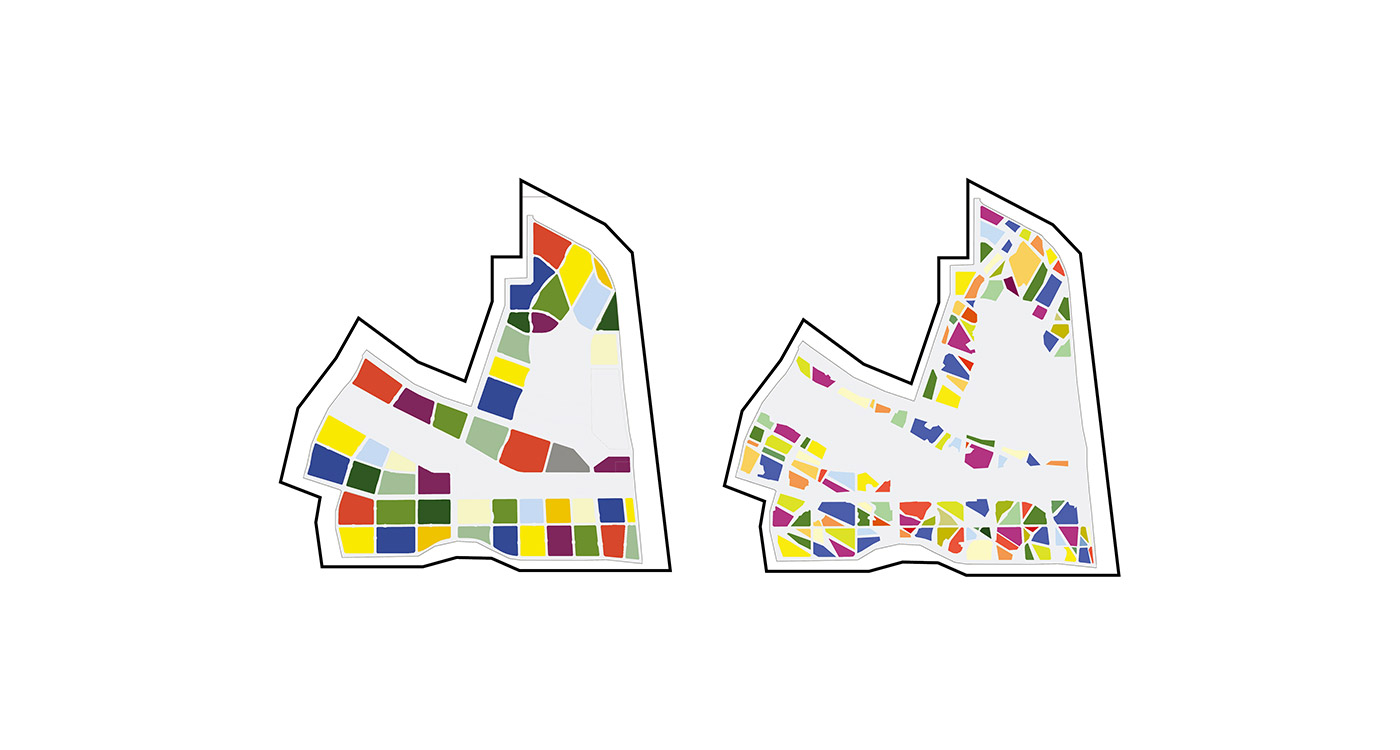

To maintain the flexibility of a residential district several options are available: the increase of commercial land-use zoning; the reduction of scale of land plots; and by flexible, or robust, site planning and building design. To maintain the government’s profit, the staging of development can be implemented in order to bring commercial projects onto the market only after the district is significantly developed. To create better cities faster, an incentive can be offered to developers willing to build commercial space in the form of a reduction of sale-cost of commercial land. Profits could be balanced by higher land sale revenues in the district due to the added amenity. Alternatively, developers can be required to demonstrate that part of their development has the potential to successfully convert to commercial use at a later date. Reducing the scale of land plots would increase the district’s potential to adapt to future demands. Currently plots are excessively large and inflexible.

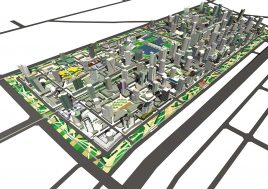

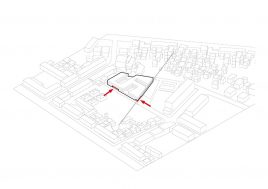

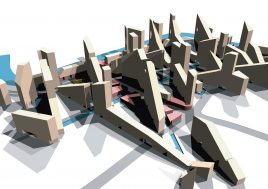

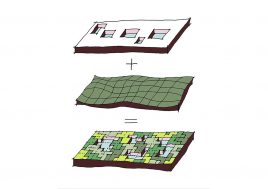

Our proposal incorporates the existing villages and tree-lined lane network into the new city. By situating the city’s regulation amount of parkland in a network form, it can follow the lanes and engulf the villages. This strategy has the benefit of dissecting the standard gigantic development sites into smaller ones of varying size and shape. This increases the flexibility, as described above, and creates more diversity as a result of the increased number of designers engaged in the district. This strategy also dramatically increases the permeability of the district, encouraging walking and cycling, and creating places for informal activity. The two city grids become superimposed: one a new super-grid of roads and the other a green pedestrian network filled with traces of the old countryside structure.

- Infrastructure

- Public

- Residential

- Healthcare

- Education

- Culture

- Office

- Retail

- Hotel

- Hospitality

- Mixed Use

- Sports

- Planning

- Urban Design

- Public Landscapes

- Private Landscapes

- Playgrounds

- Structures & Pavillions

- Residential

- Healthcare

- Education

- Culture

- Office

- Retail

- Hotel

- Hospitality

- 2021

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2005-2010

- 2000-2005

- 1990-2000

Back to projects

Back to projects